It is unfortunate that war ever broke out between Italy and Greece. The two countries share a great deal of history between them. In ancient times, Greece was part of the Roman Empire and many prominent Romans in the time of the republic and many Roman Emperors were greatly attracted to Greek culture and Greek scholars played a significant role in making Imperial Rome as great and advanced as it was. During the era of the Byzantine Empire, Italians were allies as well as antagonists. In the last days of the empire, during the siege of Constantinople, many of those defending the city from the Ottoman Turks were Italian mercenaries from the great city-states. During the Greek War for Independence, many Italians volunteered to fight alongside the Greeks. At one time, King Vittorio Emanuele II hoped that his younger son, the Duke of Aosta, might become the King of Greece to further cement Greco-Italian ties. During the struggle for Crete many Italians volunteered to fight with the Greeks even before all of Italy had been liberated from foreign control. Giuseppe Garibaldi II was only one of the many Italians who fought for Greece in the 1897 war with Turkey over Crete.

|

| Metaxas regime in Greece |

|

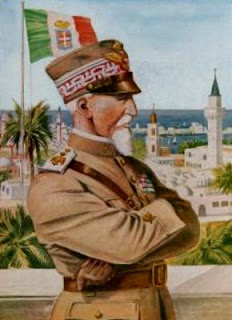

| Generale Tellini |

Unfortunately for Rome, Italy was not prepared for a war with Greece. Mussolini eagerly believed those who downplayed the strength of the Greek military and exaggerated the number of Italian warplanes, artillery and munitions. Marshal Pietro Badoglio argued that it would take at least twenty divisions to attack Greece, even with only the minimal goals of some minor gains in the Epirus region, a very rugged area. However, Mussolini listened to his general in Albania who said that the forces already deployed, reinforced by only three extra divisions, would be sufficient to defeat the Greeks. Even when Italian intelligence learned that Greece had a far larger army than previously thought and all concentrated in the mountains near Albania, General Visconti Prasca, failed to pass this information on and continued to assure Mussolini that the Greek army numbered only about 30,000 men who could be easily swept aside by the veteran Italian forces. Nonetheless, Mussolini sent Metaxas an ultimatum demanding that Greece allow Italian forces to occupy key strategic points. Metaxas was a proud nationalist and would never accept such an ultimatum. Additionally, France and Great Britain had already given a war guarantee to Greece which would have discouraged the Greeks from making any concessions for the sake of peace. As Metaxas said, “Well, it is war”.

|

| Primitive transportation |

Nonetheless, the Italians were tenacious fighters as well and their performance during the Greek War is one of the most unfair mischaracterizations in history. Italian troops advanced 40 km into Greece along the coast while battle-groups detached from the Julia Alpini Division overcame rugged terrain and heavy Greek resistance to secure the Metsovon pass while the Littoral Group and Aosta Lancers established a bridgehead across the Kalamas River, enabling the Julia Alpini to fend off heavy Greek counter-attacks by General Papagos who was trying to surround them, holding out until the Bersaglieri arrived to break the Greek ring of fire. Italian forces dug in and waited for re-supply and reinforcements but were slowly pushed back by heavy Greek attacks. Those forces along the coast also came under overwhelming attack and were pushed back, giving ground grudgingly but taking heavy casualties until some Greek forces pushed beyond the border into southern Albania.

|

| MVSN troops on the Albanian front |

|

| Carabinieri on guard in Greece |

|

| Alpini at the Parthenon |

Another point which must be made is that there was never any plan to conquer all of Greece as some seem to imply. Mussolini stated his goals for the war were the annexation of the disputed Epirus region to the Kingdom of Albania, the restoration to Italian rule of those islands which had previously belonged to Venice and the replacement of the Greek government with one more friendly to Italy. Still confident, at that point, of victory over the British, Mussolini also planned to compensate Greece for her losses by giving the Greeks the island of Cyprus. The war was though an unfortunate affair for everyone involved. However, though the Greeks were understandably bitter and being under Italian occupation in most cases, they later realized that being under German occupation was far worse when the King of Italy dismissed Mussolini and Italy withdrew from the Axis pact. We can also highlight the positive cases of when, just like in the old days, the Greeks and Italians fought together instead of against each other such as in the heroic case of the island of Cefalonia where soldiers of the Italian Royal Army fought to defend the island and the local Greek populace from Nazi occupation. It was a courageous and compassionate affair and provides a thankfully positive note to end on.

.jpg)