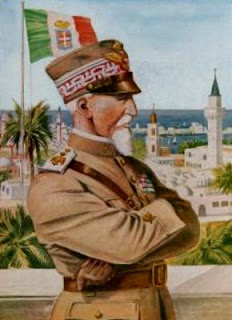

One of the most senior but actually least involved military leaders of the final years of the Kingdom of Italy was Marshal Emilio De Bono. He was born on March 19, 1866 in Cassano d’Adda in the Province of Milan. His father had been an officer in the Piedmontese army and arrived in Cassano in 1865. He met Emilia Bazzi, the daughter of a pharmacist, married her and Emilio was born soon after. As his father had been a career officer in the royal army it was perfectly natural for Emilio De Bono to choose the military life as well. He first attended the Milano Military College and then went on to the Modena Military Academy, graduating as a lieutenant in 1886. He volunteered for service in Africa and was sent with the III Bersaglieri regiment to the colonial conflict in Eritrea. His dedicated service earned him fairly steady promotion and by the outbreak of the war with Turkey in 1911 he was a lieutenant colonel. During that war De Bono saw his first service in Libya where he organized the naval supply bases at Misurata before being appointed chief of staff of the first special division.

When the Kingdom of Italy entered World War I, Colonel De Bono was chief of staff for the II Army Corps but he soon took a field assignment as the commander of the XV Bersaglieri regiment. The following year he was promoted to command the Trapani Brigade and won high praise for his actions in the capture of Gorizia in August. De Bono was promoted to general and given command of the Savona Brigade and later he was given command of the IX Army Corps which he led to victory at Monte Grappa in 1918, a feat which inspired a popular war song. As he had been at the beginning, General De Bono was there at the end as well, leading his men with reliable skill at the crushing Italian victory of Vittorio Veneto which finally forced Austria to agree to an armistice and exit the war. He was highly decorated for his service and assigned garrison duty in Verona. However, the government handling of the war, the peace settlement and the rise in radical Marxist organizations calling for the overthrow of the Kingdom of Italy pushed General De Bono into sympathy for the National Fascist Party of Benito Mussolini. It is important to note, however, that De Bono was not in favor of what the original Fascist program had been and his support, like that of many others, came after Mussolini considerably moderated his party platform for practical reasons.

General De Bono was always a patriotic Italian and a loyal subject of his King who, unlike Mussolini, believed in the monarchy as the embodiment of the history of Italy. De Bono became very close friends with Prince Emanuele Filiberto, Duke of Aosta who was also, of course, a monarchist but who also supported a more Italian nationalist position to strengthen, unite and embellish the country. De Bono had no experience in politics and no real interest in politics but he gave his support to the Fascists simply because they seemed to be in the best position to save Italy from the Marxist revolutionaries and build a more strong and proud country. Because he was so respected, and a general, the Fascists used De Bono to add respectability to their movement and capitalize on his fame. He was made inspector of the Blackshirt squads but was unimpressed with their discipline. Still, he served as one of the “Quadrumvirs” in the Fascist “March on Rome” on October 28, 1922. After the Fascists took power, De Bono was put in charge of turning the Blackshirts into a part of the national establishment, the result being the formation of the MVSN or National Security Volunteer Militia. This upset some of the older hard-line Fascists as it meant that many army veterans, who were royalists, being put in command of Blackshirt units.

After Mussolini firmly established himself as leader of the government, General De Bono was put in charge of Public Security, as the most senior military man in the Fascist hierarchy, and was appointed to the Italian Senate. In 1925 he was given the post of Governor of Tripolitania in Libya where he had to deal with rebellions by the Senussi Islamic sect. He also promoted the establishment of a modern system of agriculture in Libya, mostly by farmers brought in from southern Italy. He held that post until 1928 and the following year supported the military campaign to permanently end the Bedouin rebellion in the colony. General De Bono continued to devote his time to colonial service and in 1935 was appointed High Commissioner of Italian Africa. He played a key role in the organization of Italian forces for the war against Ethiopia and when the war began was the top Italian commander in the field. He won all of the early battles in the conflict but Mussolini was displeased by the slowness of his advance. General De Bono had planned and was waging a traditional colonial war which meant that he would keep his forces together, advancing slowly, from one defensive position to another and allowing the more numerous Ethiopians to destroy themselves by attacking the Italians with their superior weaponry in protected positions.

This was a cautious, effective strategy intended to save Italian lives. However, the sanctions imposed on Italy by the League of Nations forced a more aggressive approach. Mussolini feared, and the League of Nations hoped, that if the Ethiopians could carry on the war long enough, the Italian people would be crippled by the sanctions and it would not only force them to retreat from Ethiopia but possibly bring down the Fascist government as well. This was a real possibility as most military experts and observers expected the war against Ethiopia to take about two years at minimum to complete. To avoid this, Mussolini replaced De Bono with General Badoglio. It was a blow to the dictator who had planned the Ethiopian War to be carried out primarily by his Blackshirt militia with a Fascist general in charge. Instead, he had to turn it over to a career army man and De Bono was, as the saying goes, “kicked upstairs” with congratulations for the victories he had won and a promotion to Marshal of Italy. A new strategy was adopted and the war that was supposed to last two years ended with the Italian conquest of the Ethiopian Empire in seven months.

Marshal De Bono continued to serve in colonial posts but became increasingly less enthusiastic about the policies of Mussolini. He disapproved of the way he seemed to be sidelining the King, he disapproved of the German-inspired racial laws of 1938 and the following year reported on the woeful un-preparedness of Italian military forces and infrastructure along the French border. Unfortunately, his findings were ignored, to the detriment of the Italian forces Prince Umberto would lead into battle against the French. Even after the outbreak of World War II, Marshal De Bono remained mostly in positions in which he could review, inspect and recommend but not command. He made a report on the Italian position in Albania pointing out that they were unprepared in terms of modern equipment, weapons and supplies for major offensive operations (which was also ignored) and he had opposed Italian intervention in World War II altogether on the grounds that the military had been exhausted by the campaigns in Africa, Spain and Albania and needed a period of restoration and modernization.

Mussolini would not listen and went to war anyway and even when Marshal De Bono was made commander of the Southern Armies, this was mostly a ceremonial position. The Marshal had disapproved of almost every action taken by Mussolini in the build-up to the war and the Duce had come to view the Marshal as being overly cautious, overly pessimistic and essentially the opposite of everything he wanted to be seen as. Sadly for Italy, Marshal De Bono was proven correct during the course of the war, particularly the crucial year of 1942 when Axis fortunes began to reverse everywhere. When Sicily itself was invaded in 1943 the Fascist Grand Council, of which Marshal De Bono was a member, was called together. De Bono, quite bravely, first proposed that Mussolini hand over the responsibilities for the military and foreign policy to someone else. When Dino Grandi boldly proposed that Mussolini step down altogether Marshal De Bono was among those who voted in favor of the proposal that Mussolini had to go. Nonetheless, he was shocked when Marshal Badoglio, appointed by the King to replace Mussolini, banned the National Fascist Party and disbanded the MVSN.

In the chaotic situation that followed, Marshal De Bono felt there had never been a greater need for the structure of the old Fascist Party with the Allies demanding total subjugation, the Nazis invading from the north and communist partisans taking up arms against their countrymen. Fearful that the communists would take over, he reported for duty in Rome, prepared to help in any way he could. He also harshly criticized the Badoglio regime for ‘screwing the monarchy’. He could neither bring himself to support Mussolini’s republican regime in the north or the Allied-controlled Badoglio government in the south. In any event, he did not have long to remain in limbo. On October 4, 1943 he was arrested by the Axis forces and put on trial for “treason” by a special court organized by the Fascist Republican Party Congress. He appealed the “guilty” verdict only because of the outrageousness of referring to his actions as “treason”. Of course, it was to no avail and Marshal of Italy Emilio De Bono was executed on Mussolini’s orders on January 11, 1944.

No comments:

Post a Comment